Conceptualizing Housing as a Common Pool Resource

The Mortgage System, Governing of the Commons and The Middle Way

If you own a home, in all likelihood you conceive of it not only as a place to live but also as a financial investment.

If you rent a home, chances are you imagine it less as a place of your own, but it still constitutes a significant (if not the significant) part of your monthly budget.

Since most people reading this will be accustomed to these two generalized forms of tenure — owning and renting — it is only natural that they feel normal. Your tenancy impacts you finances, and your finances impact your tenancy. Most people start out as obligate renters, and most people strive to purchase a home for both housing and financial security. That’s just the way it is.

Today our housing is privatized and financialized. As I previously explored, the financialization of housing is a key factor in both the creation and persistence of the current housing unaffordability crisis. In response to this crisis, and despite ignoring its origins, certain voices call for greater deregulation of the private construction industry and their supporting financial systems, while others voices advocate for a return to greater public investment in social housing. Here I want to propose an alternative, third way - a kind of radical beat zen global reclaiming of housing stock for collective benefit.

Here is the idea :

Although the way we think and talk about homeownership today may feel permanent and immutable, people have not always conceptualized housing as we do. In fact, these thoughts are social constructs and have evolved over time and in different geographically and historically specific ways. Homeownership is often seen as a natural milestone of adulthood, but it is in fact a constructed normalcy shaped by postwar policies and cultural narratives.

In her work Urban Warfare : Housing Under the Empire of Finance, Raquel Rolnik outlines a global overview of the evolution of the mortgage system and its imposition on the global south through specific structural adjustments. The book details a complete shift in the concept of government’s role in housing. Whereas governments in Europe had actively provided housing assistance through the creation of a public stock of social housing, regulation of private rental and direct aid for rent payments for much of the twentieth century, the financial crisis of the 1970s lead to fundamental transformations in these attitudes and policies. New economic policies pushed by forces such as the World Bank told governments to change course :

“Their role was henceforth to create conditions, institutions and regulatory models that would promote housing financial systems capable of enabling home purchase.”1

Since this time, public policies realigned away from public housing and towards models promoting private homeownership. Certain governments such as the United Kingdom and the United States were early adopters of these new cultures. In the UK, while council housing was the main form of housing provision between the end of the second World War and the 1970s, the Housing Act of 1980 introduced a scheme called the “Right to Buy”, which allowed tenants of social housing to purchase their homes at a discounted rate, well below market value.2 This policy, accompanied by many other realignments, greatly reduced the available stock of social housing units in the UK.

Similar trends unfolded in the United States also. New housing policy changes were justified by new Neoliberal ideologies which argued the (1) imperative to reduce government spending and (2) the belief that the government should get out of the way of the “free” market. However, as we ought to be accustomed to by now, these arguments were disingenuous. The true outcome of the transformation was not actually a reduction in spending but rather more accurately a redistribution of these ressources. As Rolnik succinctly states,

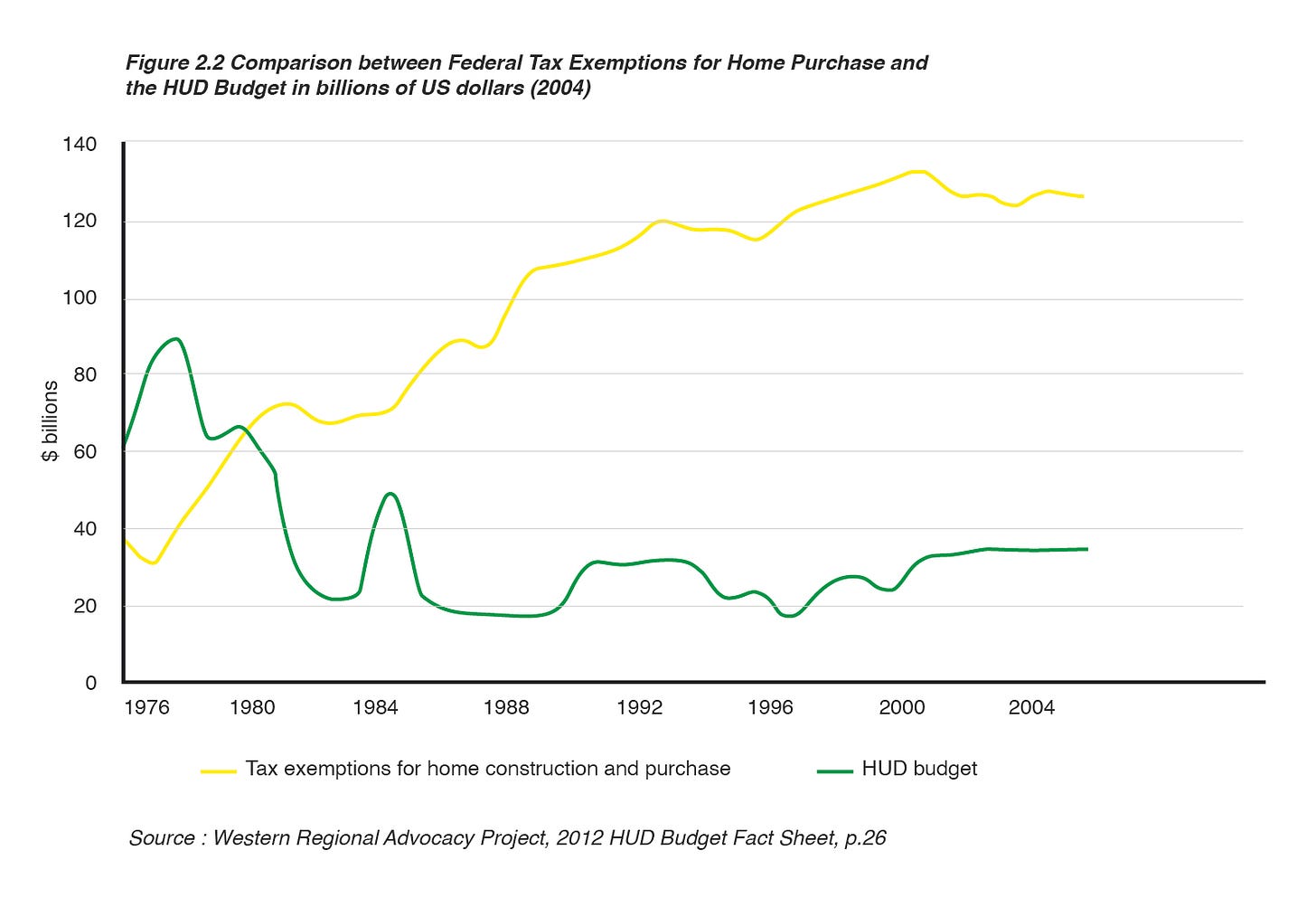

“In the US, although the HUD [Housing and Urban Development] budget has dropped, between 1976 and 2004 public expenditure on housing did not stop growing; only it was, instead, directed to higher-income sectors through tax exemptions for home purchase, as shown in figure 2.2.”

These models were exported around the world and adopted by countries nearly everywhere. The privatization of formerly public housing, reform of rental regulations, the reduction of tenant protections and subsequent increase in tenant insecurity were all features of the evolution, not bugs.

“Even where the privatisation of public stocks was not drastic, the ideological transferral of the responsibility for housing provision to private markets was hegemonic. The paradigm of ‘homeownership’ became virtually the only housing policy model.”3

Even in countries like the Netherlands and Sweden, where social democracies ensure many public support systems, public housing and rent protection wained, and the attitudes towards housing began to change :

“… beyond the elimination of social housing from the economic and social landscape, a deep transformation in its socio-cultural and political meaning is manifest. Clearly, actors involved in the production and consumption of social housing lost out to the rise of not only homeowners but, above all, real estate developers and financial intermediaries.”4

It is understandable why, when faced with this history, some people advocate for a return to the previous paradigm of public investment in social housing stock and the re-regulation of private rental markets. However, nostalgia for the past often views history through rose colored glasses and ignores certain inconvenient realities about it. For example, in the formerly Communist countries of South Eastern Europe and Central Asia (where housing provision had been an obligation of the state and homelessness was close to nil) while housing was made available,

“This is not to say that public housing projects were of a high standard, well located or fairly allocated among those in need. Large housing complexes were usually built using low-cost prefabricated technology of very poor quality. Moreover, many families and individuals had no option but to share overcrowded and precarious apartments and houses. Often these complexes were residential-only, with no social, sports or cultural facilities, and inadequately maintained. Privileged allocation of the better apartments to party or union leaders was also a common practice.”5

The truth of the matter is that the questions of housing quality and equitable distribution of housing are persistant problems that neither public nor private approaches to housing have proven themselves able to address meaningfully. I also hope to draw attention here to the psychological transformations that were necessary in the minds of people all around the world in order to facilitated the changes in housing responsibilities. The recognition of this transformation also implies an acknowledgement that these conceptions are flexible and can change again — that is, they are an expression of the power of our neuroplasticity.

If we want to respond adequately to the housing crisis, we need to build new concepts about housing.

To this end, it occurs to me that the argument about public versus private management of housing echos the research of Elinor Ostrom and her studies of the collective governance of natural ressources. Although my reading of Ostrom’s research is far from typical, I believe it can offer opportunities to rethink our concepts of housing in important and timely ways.

Ostrom received the Nobel Prize in economics for her research that problematized and debunked Garrett Hardin’s model of the Tragedy of the Commons. Briefly, Hardin argued that natural ressources that were open to all — a commons — were doomed to be over exploited. He argues that each individual acting in their own self interest had no incentive not to overuse the ressource, as whatever they did not use of it would be used to the advantage of another. His model was widely influential and served as the foundation for structuring many of our occidental concepts of natural resource management and policy.

In response to the Tragedy of the Commons, two main camps emerge claiming to be the sole solution to the imagined problem. In the first, the commons must be subdivided and sold to private individuals. In the second, an external public authority must manage the ressource to ensure its proper use.

“Garrett Hardin argued a decade after his earlier article that we are enveloped in a “cloud of ignorance” about “the true nature of the fundamental political systems and the effect of each on the preservation of the environment”… The “cloud of ignorance” did not, however, prevent him from presuming that the only alternatives to the commons dilemma were what he called “a private enterprise system,” on the one hand, or “socialism” on the other…”6

This kind of either-or thinking is a fallacy. These positions have subsequently taken on ideological dimensions and seem mainly to serve to support the underlying assumptions of those who are all too willing to accept them on face value. Our belief systems and attitudes towards human nature and natural ressources shape our views of this dilemma. On one side, those who harbor libertarian greed-is-good, nature is there for our exploit kind of mentalities feel able to justify their self interested positions. On the other side, those who long for a strong, benevolent, Leviathan protector figure who can look after the common interest give themselves permission to passively abdicate their social responsibilities to the State.

In buddhist thought there is a concept called The Middle Way. It is a discursive tool that is meant to help us break through such false dichotomies. In speaking of The Middle Way, my Zen teacher Paul reminds me that,

“It is not a way, and it is not in the middle.”

Paul describes the concept as just dealing with things the way that they are. It is about not having some preconceived idea about a given thing. The Middle Way is not being predetermined. He refers to a line in his touchstone Genjo Koan, wherein Dogen Zenji describes the Buddha way as

“leaping clear of the many and the one.”

In her own way, Ostrom thoughtfully and meticulously breaks down these opposing “only way” arguments and finds a middle way. She does this convincingly through the detailed study of existing real world examples that prove both greater complexity and hybridity in forms of collective organization. In truth, such a dichotomy is not realistic. As Ostrom points out,

“Institutions are rarely either private or public — “the market” or “the state.” … In field settings, public and private institutions frequently are intermeshed and depend on one another, rather than existing in isolated worlds.”7

She points to examples which show that far from there being one, exclusive and ideological solution to the management of generalized theoretical natural ressources, in truth there are many site-specific and varied ways to manage or mismanage a shared ressource.

“Instead of there being a single solution to a single problem, I argue that many solutions exist to cope with many different problems. Instead of presuming that optimal institutional solutions can be designed easily and imposed at low cost by external authorities, I argue that “getting institutions right” is a difficult, time-consuming, conflict-invoking process. It is a process that requires reliable information about time and place variables as well as a broad repertoire of culturally acceptable rules.”8

For those of us who advocate for the right to housing, while it feels easy to demonstrate how the current privatized management of housing has obviously failed to provided good quality housing for all, it can be harder to accept that deference to some National or Public Authority is no guarantee of a good outcome. But Ostrom points to instances that show just that :

“Relying on metaphors as the foundation for policy advice can lead to results substantially different from those presumed to be likely. Nationalizing the ownership of forests in Third World countries, for example, has been advocated on the grounds that local villagers cannot manage forests so as to sustain their productivity and their value in reducing soil erosion. In such localities, villagers had earlier exercised considerable restraint over the rate and manner of harvesting forest products. In some of these countries, national agencies issued elaborate regulations concerning the use of forests, but were unable to employ sufficient numbers of foresters to enforce those regulations. The foresters who were employed were paid such low salaries that accepting bribes became a common means of supplementing their income. The consequence was that nationalization created open-access resources where limited-access common-property resources had previously existed. The disastrous effects of nationalizing formerly communal forests have been well documented for Thailand, Niger, Nepal and India.”

Ostrom goes on to offer multiple case studies of natural resource systems that have been effectively owned and managed collectively. From fisheries in Turkey, to pasture lands in Switzerland, forests in Japan, and irrigation systems in Spain, each relying on institutional frameworks and social architectures that are specific to the culture and norms of each place.

I began to wonder what would happen if we conceptualized housing in such a way.

There are many examples of cooperative building projects and collective forms of land ownership. For example, Ebenezer Howard’s model of the Garden Cities, where land was owned by a private company made up of city residents that acted as a municipality to redistribute rent and taxes back into the town. Community Land Trusts in the United States followed suit with their own specific operating mechanisms to share land and combat speculative development. In fact, Project Row Houses, which I discuss in a previous essay, organized a CLT of their own. However, the houses which sat atop these collectively owned land ressources were still privately bought and sold — albeit with certain rules and restrictions on their modification and the profit permitted at sale.

Strictly speaking, I know of no examples of conceptualizing housing as a common pool ressource. Nor have I found any information that suggests that Ostrom had considered the question of housing within her own research and frameworks. (If you have, please let me know.) Therefore, I would like now to creatively misuse her research to explore just such an idea !

Let us imagine for a moment what it might look like if housing was a Common Pool Ressource (CPR). All of the housing is owned by everyone. There are exchanges that help homeowners step off the ladder of personal debt — and wealth — that they have accumulated and that help those who had previously been renters to earn equity for rent payments (including past payments).

Imagine one scenario, where the aforementioned questions of housing quality and the equitable distribution of housing are considered in radically new ways. In discussing the demand for housing quality, Manuel Aalbers describes metrics for what he calls “better housing position” in these terms :

“… a better-equipped residence, a larger house or a better location.”

While as an artist and designer I do not agree that these indicators circumscribe all that can be understood as housing quality, I accept that in terms of the housing market they are clearly the mesures by which housing gets categorized, priced and unequally distributed. Taking inspiration from the success of the Alanya inshore fishery in Turkey, this question of better and worse housing position can be reimagined through a system of rotation :

Early in the 2030s, members of the local cooperative began experimenting with an ingenious system for allotting housing sites to local residents. After more than a decade of trial-and-error efforts, the rules used by the Alanya Housing Commons are as follows :

Each September, a list of eligible tenants is prepared, consisting of all registered residents in Alanya, regardless of co-op membership.

Within the area normally inhabited by Alanya residents, all usable houses and housing locations are named and listed.

These named housing locations and their assignments are in effect from January through December of the following year.

In September, the eligible residents draws lots and are assigned to the named housing locations.

The system has the effect offering each tenant an equal chance to live in the best spots. The list of housing locations is endorsed by each tenant and deposited with the mayor and local gendarme once a year at the time of the lottery. The process of monitoring and enforcing the system is, however, accomplished by the residents themselves as a by-product of the incentive created by the rotation system. Attempts to cheat the system will be observed by the very residents who have right to be in the best spots and their rights will be supported by everyone else in the system. This is because the others will want to ensure that their own rights will not be usurped when they are assigned good sites.

Although this is not a private-property system, rights to use housing sites and duties to respect these rights are well defined. And although it is not a centralized system, national legislation that has given such cooperatives jurisdiction over “local arrangements” has been used by cooperative officials to legitimize their role in helping to devise a workable set of rules.

Such an arrangement may sound farfetched to our ears today, but this only highlights the psychological work necessary to build Common Pool Resource housing systems. There is nothing impossible about such a system of housing rotation. If it sounds strange to us, it is simply because we are not accustomed to it. After living with it, people might find that they enjoy the opportunity to change homes and experience different living environments more than their prior housing conditions. The fact that moving becomes an annual task would also encourage reflections on how many possessions home owners are willing and wanting to accumulate individually or may encourage co-op tenants to consider how their furnishings might also become mutualized. This would all be part of how we build new concepts of inhabiting and cohabiting our homes, our neighborhoods and our world.

If housing were collectively owned, maintenance and repairs would likely be more equitably prioritized. In our current system, privately wealthy individuals progressively improve their relative housing position by building out extensions to their homes, paying for other aesthetic upgrades, or checking off “comps” to increase the value of their home. A collective ownership would incentivize improvements to the least equipped, smallest and worst located housing first, because the lottery and rotation systems makes not only possible, but statistically inevitable that each resident will have to live in the poorest quality housing. Everyone would benefit from improvements made to the housing in greatest need. Progressively, this could contribute to a phenomena that encourages gradual improvements to all the housing stock eventually working up to making elective improvements to the good housing to make them even better.

These are but a few of the implications inspired by but one form of collective resource management in the repertoire of Ostrom’s field work. One of her aims in Governing the Commons is to distill what is essential to the success of long standing CPRs. To this end, she outlines a series of key features to all successful examples that she studied. The following “design principles” are used to structure the collective organizing :

Clearly defined boundaries

Congruence between appropriators and provision rules and local conditions

Collective-choice arrangements

Monitoring

Graduated sanctions

Conflict-resolution mechanisms

Minimal recognition of rights to organize

Nested enterprises

Suggesting such a reform leaves important questions to be answered regarding the appropriate scale of the collective ownership, the attribution of responsibilities for the maintenance of a local housing stock and how they get shared between local actors, and how these local housing CPRs get nested into neighborhood, community, or regionally managed structures? The people who form the CPRs will need to discuss, debate, determine and subsequently possibly even modify their rules. As Ostrom acknowledges, the act of organization building is protracted, laborious and often conflictual. But this is understood as the price of entry into a system of commonly pooled housing.

Governing a housing commons may not prove simple, but I believe it to be possible and perhaps even a better alternative to the current options offered by the paradigm of the opposing “only way” Public vs. Private regimes. It will require more active participation and a generous dose of creativity to imagine such a shift. When the Tragedy of the Commons is studied in game theory, it is described as a “prisoners dilemma”. The players are captive to larger systems that are unknowable to them and they are isolated from the other participants.

“The participants may simply have no capacity to communicate with one another, no way to develop trust, and no sense that they must share a common future. Alternatively, powerful individuals who stand to gain from the current situation, while others lose, may block efforts by the less powerful to change the rules of the game.”9

If we struggle to imagine an alternative to privately owned and financialized housing, or its public option predecessor, it may be because the paradigm serves the needs of certain players.

For the rest of us, let us not be fooled — we share a common future and we can change the rules.

Rolnik, Raquel. Urban Warfare: Housing Under the Empire of Finance. Translated by Gabriel Hirschhorn. London: Verso, 2019, p. 24

Ibid, p. 30

Ibid, p. 25

Ibid, p. 54

Ibid, p. 66

Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 9

Ibid, p. 15

Ibid, p. 14

Ibid, p. 21